Economic Transformation: A Wellbeing Economy?

Thursday 9 February 2023, at the Scottish Parliament

With Scotland facing the challenges of a climate and ecological emergency, rising inequality and an ageing population, new ideas of how our economy could, and should, work are taking hold.

This seminar looked at the idea of a wellbeing economy: what does it mean and what would it look like in Scotland?

Podcast

https://scottishparliament.podbean.com/e/a-wellbeing-economy-in-scotland/Introduction

The Scottish Government’s 10-year National Strategy for Economic Transformation (NSET) sets out an overriding vision to deliver a wellbeing economy for Scotland, which it defines as an “economy where good, secure and well-paid jobs and growing businesses have driven a significant reduction in poverty”.

This seminar, with the Wellbeing Economy Alliance, offered participants a chance to consider what that means, what it might look like and what difference it would make.

The seminar featured presentations from Dr Lukas Bunse and Frances Rayner from the Wellbeing Economy Alliance Scotland, and reflections from political economist Miriam Brett and Simon Farrell, former co-owner and managing director of one of the UK’s most successful brand agencies.

It was held in conjunction with the Scottish Parliament Information Centre.

Presentations

Introducing the Wellbeing Economy: Frances Rayner and Dr Lukas Bunse

Frances introduced WEAll Scotland as one of a growing worldwide network of hubs that make up the Wellbeing Economy Alliance. In this, various think tanks, organisations, academics and economists are testing different approaches to the economy that respect planetary boundaries and deliver for humanity.

As she described, the movement is about learning from each other and working together, and in the past 18 months it has been getting started in Scotland.

First, Frances addressed the question of why we need a wellbeing economy at all. As she noted, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change recently warned that we have a rapidly closing window in which to secure a liveable planet, and the effects of climate change are starting to be felt close to home.

She also highlighted the effects of inequality, pointing out that, even before the pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis, one child in four in Scotland was growing up in poverty, while the 20 richest families currently own as much wealth as 1.6 million people.

Frances argued that we have inherited an economic model that is not working, and which has not yet been updated. At its heart is the goal of growing GDP, on which most of our economic decisions are focused. However, as she described, GDP measures only the exchange of goods and services and fails to distinguish between what we need and value and things that cause harm.

For example, GDP may capture a positive impact from natural disasters that create new jobs in construction, but it does not encompass things like unpaid childcare, on which our society and economy rely. Frances emphasised that the continual pursuit of GDP is causing environmental damage and is a big factor in climate change.

Summing up the context for a new approach, Frances argued that we currently put a lot of effort and resource into failure demand: fixing the problems that our current flawed approach creates. For example, we spend money to house people who are living without homes, rather than asking what the tax system might look like if we decided that no level of poverty was acceptable.

Frances emphasised that the wellbeing economy approach puts very different goals at the heart of economic decision-making. She outlined five key principles:

- Dignity – everybody has enough to have their needs met.

- Purpose – institutions serve the common good.

- Nature – a restored and safe natural world.

- Participation –people can participate in decisions that affect their lives.

- Fairness – income and wealth are more fairly distributed.

Lukas moved on to consider a key question: how do we get to a wellbeing economy? He stressed that a big shift is required, with four design principles at its core:

- Purpose – Embedding the purpose of serving the needs of collective wellbeing for people and planet at the heart of decision making in economic policy and more widely.

- Prevention – Tackling the root causes of problems instead of simply assuaging harms, and designing our economy in order to mitigate climate change and centre preventative investment.

- Pre-distribution – Designing an economic system that does not generate inequality in the first place and looking at how we democratise ownership of assets and design our economy differently.

- People power – Most importantly, a wellbeing economy cannot be designed from the top down but needs to be built through meaningful and broad engagement with the people whom it is meant to serve.

Lukas highlighted the Scottish Government’s commitment to a wellbeing economy and assessed the level of progress that Scotland had made so far. He argued that while the Government’s National Performance Framework and tools such as the Wellbeing Economy Monitor represent a good start, they do not influence decision making to a great extent and are not as participatory as they could be.

In addressing the question of how we move forward, Lukas highlighted inspirational examples from elsewhere. For example, New Zealand has started building its budget around wellbeing priorities; the Future Generations Commissioner in Wales provides scrutiny, advice and support around the wellbeing economy agenda, and the Citizens Council in East Belgium comprises randomly selected citizens who facilitate citizens’ assemblies and scrutinise the work of the Parliament.

Lukas described some interesting first steps that have been happening in Scotland. The Business Purpose Commission for Scotland has recently reported, and innovative community wealth building approaches are being implemented in North Ayrshire and elsewhere.

In addition, Lukas highlighted that a lot of thinking and work is going on around the concept of a just transition. However, he reiterated that those elements do not yet add up to the systemic change that we look for in a wellbeing economy. He stressed that we need to be bolder and go much further.

Lukas noted that there is a lot of demand for ideas, such as a minimum income guarantee and universal basic services. He argued that more could be done to support co-operative social enterprises and consider public ownership where that made sense.

Reflections

Opportunities for Scotland: Miriam Brett

Miriam began by outlining the context: the causes and distributional consequences of climate and environmental collapse are felt unevenly within and between global regions and countries and are inherently unequal.

There is vast inequality in carbon emissions and consumption, with the richest 10 per cent globally consuming 48 per cent of global CO2 emissions. Structurally oppressed groups are often least likely to cause climate and environmental breakdown, but they are disproportionately bearing the impact.

Miriam emphasised that, in this context, marginal and timid measures will not suffice; there is very limited time left for us to turn the ship around.

Miriam set out three key priority areas for a wellbeing economy in Scotland:

- land reform;

- energy systems in conjunction with community wealth building; and

- a net zero industrial strategy.

Land reform: implications and issues for rural communities

Miriam argued that land is integral to securing a wellbeing economy, encompassing issues such as nature restoration, rural housing justice and biodiversity protection.

She highlighted the pressures on Scotland’s land market such as intense concentration of ownership, light regulation and a generous subsidy regime.

The purchasing of rural land by businesses to offset carbon emissions has wider implications for rural communities, including higher rents and the inability for those communities to secure their economic potential. Miriam also raised the broader question of whether this is just an opportunity for major polluters to offset their emissions rather than reducing them directly.

Noting that a new land reform bill is on its way, Miriam highlighted some aspects that it will need to address:

- It should strengthen community right to buy.

- It should introduce a new statutory power to apply a public interest test to large land holdings.

- It should create a mandatory system of certification for carbon credits.

- It should secure the longer-term ambition of creating and introducing a land value tax.

Energy systems and community wealth building

Miriam indicated the need for local economic systems change and the transfer of physical and financial assets into the hands of local communities and economies. She identified five key pillars of community wealth building:

- Plural ownership of the economy.

- Making financial power work for local places.

- Fair employment and just labour markets.

- Progressive procurement of goods and services.

- The social production and social use of land and property.

Miriam pointed to energy systems as a particularly important issue that could be addressed through community wealth building. As she outlined, the current energy crisis shines a spotlight on the long-standing failures and fault lines inherent in our privatised, deregulated energy system.

She described how community energy systems ownership could work through the creation and establishment of municipal energy companies that can develop, own and deliver low-carbon heat and energy-efficient infrastructure, highlighting North Ayrshire Council’s innovative work in that field.

A net zero industrial strategy: decarbonisation and democratisation

As Miriam noted, Scotland’s economy is still heavily reliant on fossil fuels. Emphasising that we are currently at a crossroads and require rapid action at all levels of Government, she argued that the state, rather than stepping in to address market failure, should instead be actively engaged in stewarding a green industrial strategy.

Such a strategy would accelerate the decarbonisation and democratisation of our economy; protect the livelihoods of fossil fuel workers and communities; build on and strengthen the fair work agenda; and enhance our green domestic manufacturing base.

Miriam stressed the need to rewire the economy to make it sustainable, democratic and fairer. Given the limited time we have left, we need to get creative and bold.

A Business Perspective: Simon Farrell

Having run his own business and worked for large independently owned businesses and small and medium-sized enterprises, Simon offered some reflections on the wellbeing economy model from a business perspective.

Simon described moving from a mindset of helping big multinationals to make more money, with success being measured by profit, to a different view of the impact on the environment and the future world that our children inherit. He highlighted the work of the B Corporation in promoting a different type of business with a different mindset, with the purpose of doing something good for society, planet and people.

Simon raised a question: how do businesses make money and employ people, while making a positive impact at the same time? As he noted, the wellbeing economy takes a similar approach to the B Corp model at a nationwide level, and Scotland is a leader in taking the concept seriously.

Simon argued that, while businesses want to make a positive impact, they often do not know how. By giving businesses and business leaders the tools to move in a different direction we can have a real impact. As he suggested, rewiring a business is much easier than rewiring the whole economy.

Simon noted that, while Scotland is a brilliant place to be for businesses who want to make a difference and be more purpose led, support is needed both culturally and through tax regimes. As he put it, changing our approach to business is not a problem to be solved, but an opportunity to be taken; it is about opening people’s eyes to the future.

Q&A session

Responding to the themes and issues highlighted in the presentations, participants raised questions around education, land reform and the broader potential for unintended consequences in moving towards a wellbeing economy.

The need to give greater thought to linking up policies and areas of Government, and the need for bold action in delivering on our aims, were discussed as key concerns.

Helping to join up the dots

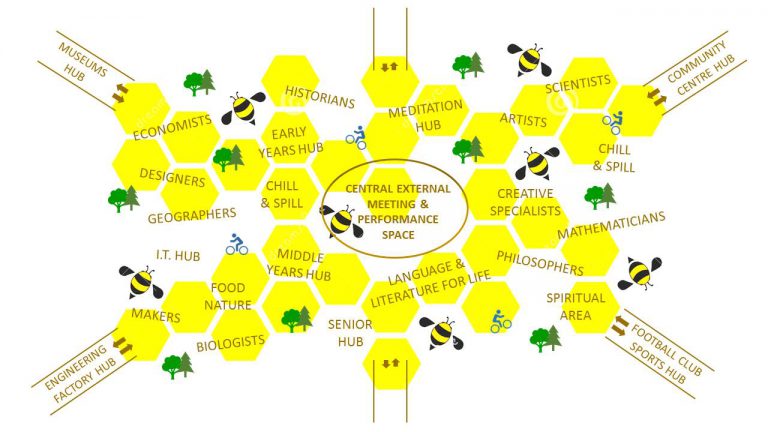

An important question was raised: how do we begin to weave green economy opportunities into our education system? As Miriam pointed out, there is now more diversity and plurality around what economics means at university level. Lukas agreed that we need to look at education as there is a long way to go, but he too noted the increasing demand for different economic thinking within universities.

The centrality of education was also highlighted in the context of SMEs. It was pointed out that, while Scotland is a country of SMEs, the majority of those businesses do not have a net zero strategy or know what it means. It was argued that education is required on how to change businesses and create opportunities, as inequality of opportunity is a drag on the green economy.

Simon highlighted the work of the Business for Good programme run by Everyone’s Edinburgh, which targets SMEs specifically. He suggested that opportunity comes in thinking about a business holistically, as evidence from the B Corp movement has shown. He agreed that it could be difficult and challenging to get the message across, although we already have the tools and training programmes to help businesses join up the dots. Lukas noted that while an initiative such as Scotland CAN B, funded by the Scottish Government, has been a great tool, it could link up better with Scotland’s enterprise organisations.

The importance of considering links between policy areas, and the need for Government to think holistically across portfolios, were highlighted as a way to avoid any unintended consequences of change. Land reform in particular was highlighted as an area in which care must be taken. It was suggested that the drive to fragment some of the bigger land holdings could result in a negative impact on biodiversity, or discourage investment.

Miriam agreed that, while democratising land is important, the approach that is taken is key. She highlighted the report that she co-authored for Community Land Scotland on community wealth building, stressing that land reform needs to work for communities in a way that creates good local jobs and promotes biodiversity and nature restoration.

The need for a tailored approach in different communities was highlighted as a way to avert any potential negative effects. As Miriam put it, the beauty of community wealth building is that it is locally led and driven, so it will look different across the country. She also highlighted examples of best practice that could be helpful and inspirational for communities, as far afield as Ohio and closer to home in Preston.

Promoting and enabling change

It was stressed that action is important, and that we need politicians who are prepared to look at things in a different way. The need for bold leadership was underlined, and Frances noted that in a time of economic crisis, pursuing a radically different approach to the economy is inherently bold. As she emphasised, it is about bringing together the public and civil society. She also noted the importance of trying to change economic commentary, so that Governments are praised when they try to do something different.

As Frances identified, we all have a role in promoting and enabling change within a wellbeing economy framework, rather than waiting for someone to show us the way. She identified that change is about process as well as leadership, with a wellbeing approach to setting budgets, for example, representing a huge institutional change.

On the question of how Government should be scrutinised, in particular by those in Parliament, Lukas reiterated that action was important. He highlighted that while the Scottish Government has a lot of positive commitments—for example, a commitment to building an economy within environmental limits—the actions are often not in place to back them up. Miriam argued that scrutiny of Government has to start with an understanding of the severity of the intertwined challenges ahead.

An outcomes-based approach

It was questioned whether, while the idea of driving forward a wellbeing economy is meant to run through the National Strategy for Economic Transformation [NSET], there are still tensions in delivery that need to be resolved.

Lukas identified conflicts in the strategy between the high-level commitment to a wellbeing economy and the delivery plans. He raised a question: do the themes that the strategy prioritises accord with a wellbeing economy approach? Lukas cited its references to entrepreneurialism focused on growth as evidence of conventional thinking creeping back in, rather than aligning actions with the goal of serving collective wellbeing on a healthier planet.

Miriam also highlighted concerns about joined up thinking across Government and, returning to the theme of unintended consequences, flagged up the potential for real inconsistencies to arise if we do not ask who may benefit from a particular policy.

She highlighted that the NSET’s focus on making Scotland a magnet for inward investment and global private capital could potentially conflict with the goals of being a wellbeing Government and embodying sustainable development.

Miriam emphasised that we need an outcomes-based approach that considers impacts, rather than defaulting to traditional economic strategies that can have a corrosive impact in terms of inequality and climate. We need to think about how different ambitions intersect with one another, and how they are geared towards overarching goals of social justice and climate and environmental resilience.

Power and control

Finally, participants picked up on the issue of tensions around governance and the role of private enterprise. It was pointed out that financial constraints on Government mean that there is increasing private sector involvement, including from banks. This may bring with it a considerable risk of embedding historical issues of power and control and limited governance over companies that operate at a global level.

Miriam again emphasised the need for bolder scrutiny within broader parameters, and the need for an interlinking approach. As participants identified, in seeking to build a wellbeing economy, we all need to get to the same place, so it is important to consider these issues in order to ensure that everyone is on board.

Panel

Frances Rayner is communications lead at WEAll Scotland. She has more than a decade’s experience in a range of communications and campaigning roles for social and environmental causes. She has led communications at Poverty Alliance and WWF Scotland and mobilised public support for climate action as Chair of the Stop Climate Chaos Scotland campaigns group.

Dr Lukas Bunse is policy and engagement lead at WEAll Scotland. He has several years’ experience researching and promoting wellbeing and post-growth economics. His PhD at the University of Leeds investigated how structural change can contribute to the creation of a sustainable, post-growth economy. Lukas holds an MSc degree in Ecological Economics from the University of Leeds and a BSc (Hons) in Sustainable Development from the University of St Andrews.

Miriam Brett is a political economist who has worked on sustainability issues for many years. A trustee of the Green New Deal Rising campaign group, Miriam has also worked with Common Wealth, a London-based think tank designing new ownership strategies for a democratic and sustainable economy, and as an expert advisory group member for the North Ayrshire Community Wealth Building strategy.

Simon Farrell is an award-winning managing director and brand specialist. Having built one of the UK’s leading brand and marketing agencies, Simon now runs business advisory firm “Today the Arena”, which acts as a consultancy for businesses with a social purpose. Like many senior leaders in business, he grew up with the ideological thread of ‘profit is progress’ but has more recently embraced purpose-driven business, helping ambitious businesses make a difference while making money.

Chair

Claire Baker MSP is a member for the Mid Scotland and Fife parliamentary region and convener of the Scottish Parliament’s Economy and Fair Work Committee.

Partners