Scottish Biodiversity Policy for the Future

Across the world mass biodiversity loss is being driven by human activities, including climate change, pollution and changing land and sea use. While international agreements and frameworks have been established to tackle this crisis, progress has so far been slow. Scotland, where biodiversity intactness is notably low, is experiencing many of the same challenges as those seen at the global level. This blog examines the obstacles which Scotland faces in achieving its current targets and explores possible futures for the country’s biodiversity, including approaches which better recognise the intrinsic merit of nature, beyond just its economic value.

Biodiversity loss: the global context

Biodiversity refers to the variety of life on Earth, including within species, between species and among ecosystems. Human activities are currently driving biodiversity loss at an unprecedented rate and scale, making it one of the most complex and urgent environmental crises.

The pace of its loss has increased substantially within the past 100 years, with over 25% of evaluated plant and animal groups now in decline.1 According to the independent intergovernmental body IPBES2, this is primarily due to:

- Changes in land and sea use

- Exploitation of organisms

- Climate change

- Pollution

- Invasive alien species

In response to this crisis, several international agreements and frameworks have been created. This includes the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and Global Biodiversity Framework.

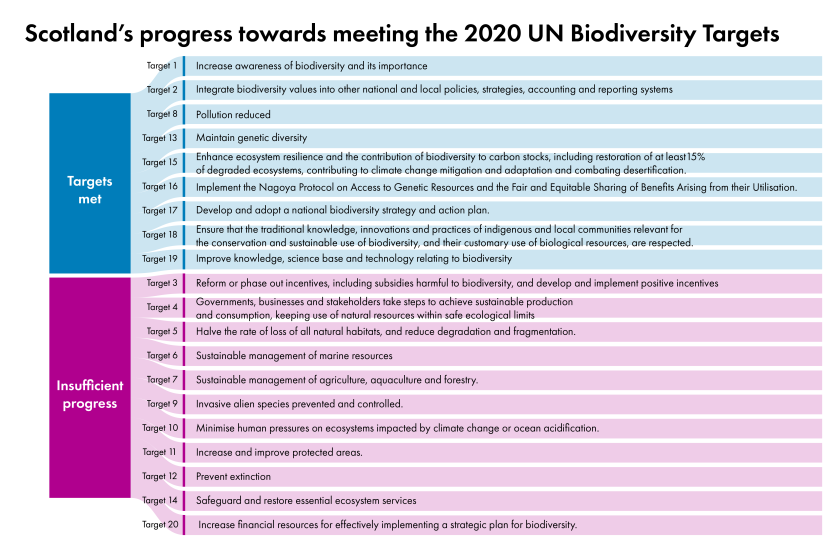

However, the progress and success of these agreements has often been limited because of factors such as state non-compliance, insufficient funding, weak national implementation and the prioritisation of other interests.3,4 An example of this is the CBD’s 2020 Aichi targets, which aimed to halt biodiversity loss. Globally, none of the 20 targets were fully met and only six were partially fulfilled.5

Scotland has also lost a significant amount of its biodiversity, ranking among the bottom 15% globally for biodiversity intactness.6 According to the State of Nature 2023 report7, Scotland is one of the countries whose habitats and species have been most impacted by human activities. This has led to a 15% decline in species abundance, with Scottish seabirds, plants and lichens among the most severely impacted.

Biodiversity loss in Scotland

The report also highlights how Scotland’s biodiversity has been affected by centuries of changing human practices, not just decades. The shifting baselines phenomenon means that people often view their own childhood as the reference point for how nature ‘should be’, rather than looking back further. To better protect Scottish biodiversity, it is therefore important to focus not just on recent trends but to also look further into both the past and future.

How is Scotland addressing biodiversity loss?

In 2022 the CBD adopted the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which contains 23 specific targets for 2030.8 This includes a commitment to conserving 30% of all land and water by 2030 (“30×30”). The UK is party to the Convention, with Scotland having devolved responsibility for biodiversity.9

To meet its obligations the Scottish Government has committed to a range of actions, including the national Biodiversity Strategy10 and Natural Environment Bill.11 The Biodiversity Strategy supports the 30×30 target and also aims for Scotland to have restored and regenerated its biodiversity by 2045. The Natural Environment Bill, which is currently being scrutinised, would create an obligation for the Scottish Government to set legally binding nature restoration targets.12

However, concerns have been raised that the current pace of progress is unlikely to be sufficient for Scotland to meet its 2030 targets.13,14 The Scottish Government has also struggled to meet previous biodiversity targets, including the Aichi targets.

International implications of Scottish policy

It is also important to consider the international implications of Scottish biodiversity policy. For example Scotland, at around 80,000sq kilometres, is home to approximately 90,000 different species.15 This means it holds only a small fraction of total global biodiversity. In comparison, Costa Rica is just over 50,000sq kilometres but is home to about 500,000 species16 (approximately 5% of all estimated species on earth).

Future approaches could therefore pay greater attention to the way in which international trade, supply chains and mass consumption damage both nature and the climate, especially within biodiversity hotspots.

Imagining future scenarios

Act now, save later17, a partnership report between the University of Edinburgh and Scottish Wildlife Trust, explores two potential economic futures for Scotland.

Scenario 1 imagines what would happen if no further significant steps are taken to address biodiversity loss. It predicts that the decline in nature would significantly weaken the economy and increase inequality, with the agricultural and tourism sectors among those most severely impacted.

Scenario 2 focuses on what would happen if a biodiversity strategy was successfully delivered. It explores a future in which “Scotland’s economic success is no longer measured by GDP but by how well a healthy economy can exist within a healthy environment” (p.9).

The report also emphasises that we should not just focus on the economic argument for protecting biodiversity, as this ignores the intrinsic value of nature and its role in our collective wellbeing. For example, other research has found that over 75% of Scottish people18 feel a connection to nature and have worried about the natural environment.

Whether or not either scenario proves entirely accurate, it is a useful thought exercise which highlights the complex social, political and economic consequences of biodiversity loss, as well as the importance of creating policy for the long-term future.

Anna MacDonald

I have been a Business Coordinator for Scotland’s Futures Forum since April 2024. I recently completed an MSc in Society, Politics and Climate Change at the University of Bristol and am fascinated by how policymakers respond to complex global environmental challenges. This blog is partially adapted from my Masters’ research project.

Sources:

- Petersson, M. and Stoett, P. (2022) Lessons learnt in global biodiversity governance. International Environmental Agreements, 22 (no issue), pp. 333–352. ↩︎

- Díaz, S., Settele , J., Brondízio E.S., E.S., Ngo, H.T., Guèze, M., Agard, J., Arneth, A., Balvanera, P., Brauman, K.A., Butchart, S.H.M., Chan, K.M.A., Garibaldi, L.A., Ichii, K., Liu, J., Subramanian, S.M., Midgley, G.F., Miloslavich, P., Molnár, Z., Obura, D., Pfaff, A., Polasky, S., Purvis, A., Razzaque, J., Reyers, B., Roy Chowdhury, R., Shin, Y.J., Visseren-Hamakers, I.J., Willis, K.J. and Zayas, C.N. (2019). Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Bonn: IPBES Secretariat. ↩︎

- Perino, A., Pereira, H.M., Felipe?Lucia, M., Kim, H., Kühl, H.S., Marselle, M.R., Meya, J.N., Meyer, C., Navarro, L.M., van Klink, R., Albert, G., Barratt, C.D., Bruelheide, H., Cao, Y., Chamoin, A., Darbi, M., Dornelas, M., Eisenhauer, N., Essl, F., Farwig, N., Förster, J., Freyhof, J., Geschke, J., Gottschall, F., Guerra, C., Haase, P., Hickler, T., Jacob, U., Kastner, T., Korell, L., Kühn, I., Lehmann, G.U., Lenzner, B., Marques, A., Motivans Švara, E., Quintero, L.C., Pacheco, A., Popp, A., Rouet?Leduc, J., Schnabel, F., Siebert, J., Staude, I.R., Trogisch, S., Švara, V., Svenning, J., Pe’er, G., Raab, K., Rakosy, D., Vandewalle, M., Werner, A.S., Wirth, C., Xu, H., Yu, D., Zinngrebe, Y. and Bonn, A. (2021) Biodiversity post?2020: Closing the gap between global targets and national?level implementation. Conservation Letters, 15 (2), pp. 1–16. ↩︎

- Ferraro, G. and Failler, P. (2024) Understanding the “implementation gap” to improve biodiversity governance: an interdisciplinary literature review. Journal of Sustainability Research, 6 (2), pp. 1–20. ↩︎

- Sun, Z., Behrens, P., Tukker, A., Bruckner, M. and Scherer, L. (2022) Shared and environmentally just responsibility for global biodiversity loss. Ecological Economics, 194 (no issue), pp. 1–10. ↩︎

- Pakeman, R.J., Eastwood, A., Duckett, D., Waylen, K.A. Hopkins, J. and Bailey, D.M. (2023) Understanding the Indirect Drivers of Biodiversity Loss in Scotland. NatureScot Research Report 1309. Available: https://www.nature.scot/doc/naturescot-research-report-1309-understanding-indirect-drivers-biodiversity-loss-scotland [Accessed: 2 October 2025]. ↩︎

- State of Nature Partnership. (2023) State of Nature Scotland Report. State of Nature Partnership. Available: stateofnature.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/TP25999-State-of-Nature-main-report_2023_FULL-DOC-v12.pdf [Accessed: 2 October 2025]. ↩︎

- Li, Q., Ge, Y. and Sayer, J.A. (2023) Challenges to Implementing the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. Land, 12 (12), pp. 1–11. ↩︎

- Brand, A. (2022) Governing nature – halting biodiversity loss. SPICe. Available: https://spice-spotlight.scot/2022/10/03/governing-nature-halting-biodiversity-loss/ [Accessed: 9 October 2025]. ↩︎

- Scottish Government. (2024) Scottish Biodiversity Strategy to 2045. Scottish Government. Available: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-biodiversity-strategy-2045/ [Accessed: 9 October 2025]. ↩︎

- Scottish Parliament. (2025) Natural Environment (Scotland) Bill. Scottish Parliament. Available: https://www.parliament.scot/bills-and-laws/bills/s6/natural-environment-scotland-bill [Accessed: 9 October 2025]. ↩︎

- The Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management. (2025) Scotland’s Natural Environment Bill: What’s included? CIEEM. Available: https://cieem.net/scotlands-natural-environment-bill-whats-included/ [Accessed: 9 October 2025] ↩︎

- Carrell, S. (2025) ‘We are resting on our laurels’: Scotland faces significant challenge to protect its environment. The Guardian. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2025/jan/19/we-are-resting-on-our-laurels-scotland-faces-significant-challenge-to-protect-its-environment [Accessed: 9 October 2025]. ↩︎

- Richard, K. (2025) A Step Forward for Scotland’s Biodiversity? Reflecting on the Scottish Biodiversity Strategy. Scottish Wildlife Trust. Available: https://scottishwildlifetrust.org.uk/2025/01/a-step-forward-for-scotlands-biodiversity-reflecting-on-the-scottish-biodiversity-strategy/ [Accessed: 9 October 2025]. ↩︎

- Scottish Government. (2023) Future of National Parks: strategic environmental assessment – environmental report. Scottish Government. Available: https://www.gov.scot/publications/strategic-environmental-assessment-sea-future-national-parks-scotland/pages/11/ [Accessed: 2 October 2025] ↩︎

- Johnston, E. (2022) Costa Rica: Paradise on Earth. Kew. Available: https://www.kew.org/read-and-watch/costa-rica-biodiversity [Accessed: 2 October 2025] ↩︎

- Daniels-Creasey, A., Metzger, M., Clough, J. and Wilson, B. (2024) Act now, save later: Scenarios of economic consequences of (in)action on biodiversity in Scotland. CFSL report, the University of Edinburgh. http://dx.doi.org/10.7488/era/5061 ↩︎

- Barnes, H. and Connolly, S. (2024) Scottish Environment LINK: Measuring public attitudes in Scotland. The Diffley Partnership. Available: https://www.scotlink.org/publication/polling-results-with-diffley-partnership-measuring-public-attitudes-in-scotland/ [Accessed: October 2 2025]. ↩︎