Future Schooling, Education and Learning: Where next for education in Scotland?

Through 2020 and into 2021, the Covid-19 pandemic has challenged us in many ways. In education, incredible change has taken place to react to the public health restrictions and to continue to provide education as well as possible in trying times.

This conference, held by the Goodison Group in Scotland and Scotland’s Futures Forum over two online sessions in November 2020 and February 2021, asked participants to take a step back from dealing with the day-to-day challenges and consider the future.

Introduction

As we continue to deal with this current reality, will the next normal in education follow the current approach to formal education and schooling but doing this more effectively? Or, as a society, will we take the opportunity to review the purpose of education and school to ensure it is relevant and sustainable for the 21st century?

To tackle these questions, a mix of people came together from the GGiS and Futures Forum community, including children and young people, educationalists, academics, people from business, the third sector and government.

Following on from the Futures Forum and GGiS project “Scotland 2030: Future Schooling, Education and Learning”, the conference explored the change that had happened already due to the Covid-19 pandemic and the change that was now possible.

Both sessions followed the format of input, breakout groups and plenary feedback.

As part of our conference, we were keen to highlight the great work and innovation already possible in Scottish education and learning, including anything that has been introduced because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The Creative Bravery Festival Team described these as ‘pockets of the future in the present.’

We had a great response to our call for short videos, and they are presented together with some additional materials on a dedicated hub.

View the videos and additional materials

Foreword by Sir Andrew Cubie

In writing this, I realised it is almost 12 months to the day since the Goodison Group in Scotland (GGiS) and Scotland’s Futures Forum (SFF) community last met in person.

In March 2020, we marked the publication of our report, Future Schooling, Education and Learning: 2030 and Beyond at an event at the Scottish Parliament. The aim of the report, with its scenario of education in 2030 at its heart, was to challenge people and stimulate their thinking about the future of Scottish education.

Over the past 12 months, the Covid-19 pandemic has been challenging us in many ways, and some aspects of the scenario have become a reality or been explored in detail. As we continue to deal with this current reality, will the next normal in education follow the current approach to formal education and schooling but doing this more effectively? Or, as a society, will we take the opportunity to review the purpose of education and school to ensure it is relevant and sustainable for the 21st century?

We acknowledge that in some shape or form conversations and activities have been ‘bubbling up’ on this topic: the Creative Bravery Festival, Exam.Scot, RSA – the Education Curriculum Reimagined: CfE2.0, the Commission on School Reform – Engaging the Disengaged event and Edujam, to name a few. These are in addition to the work of the OECD, the International Council of Educational Advisers (ICEA), and the Additional Support for Learning Review.

As a GGiS/SFF collaboration, we thought there was merit in considering what we need to think about for the next normal in education to emerge, and to do this by continuing to use a scenario approach, creating a link with our previous report.

Our intention is to provide a safe space for discussion and reflection; hence our sessions are held under the Chatham House Rule. We believe that using a scenario approach helps facilitate this, by considering possible futures and thinking creatively about how we get there.

To be clear, the scenarios we use are not predictions and we acknowledge there are other options to be explored.

In exploring the questions that we should be asking ourselves at this point in time, along with assessing the potential effect of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, our conference looked to identify the levers, acceleration points and acupuncture points for change. We were delighted to be joined by a wide range of voices, including those of children and young people, educationalists, and policy makers.

This conference was not only about discussing what we need to change or introduce in Scottish education. Our aim was also to highlight and build upon the great work and innovation already possible in Scottish education and learning, including anything that has been introduced because of the Covid-19 pandemic. The Creative Bravery Team described these as “pockets of the future in the present.”

We asked for examples from individuals (children and young people, teachers, parents and lecturers), from schools, colleges and universities and from organisations, who, in relation to learning and education, have approached things differently.

I am grateful to all those who joined us for this conference, and I hope this report will provide useful material and insights, positively contributing to the current discussions and debates on the way forward for Scottish education.

Context

“Unless educators focus on teaching the skills that are uniquely human – independent thinking, teamwork, and caring for others – kids don’t stand a chance. If we do not change the way we teach our children, in 30 years we will be in big trouble.“ Jack Ma, former head of Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba, World Economic Forum in 2018.

“The skills needed include ‘problem-solving, collaborative problem-solving and ‘global competencies’, such as open-mindedness and the desire to make the world a better place… creative thinking, [and] habits of creativity such as being inquisitive and persistent.“ Andreas Schleicher, Head of Education at OECD.

We and others have documented that the future for our children and young people will be increasingly complex, a world where fast-paced change will be the norm. However, whatever the future may bring, any education system needs to engage with, challenge and influence these changes, as well as help prepare children and young people to navigate this future world, to contribute, to thrive, and to become lifewide and lifelong learners.

Conference Format

This report summarises the key inputs, discussion points, questions and ideas from a conference held over two sessions in November 2020 and February 2021. Taking part were a mix of people from the GGiS/SFF community, including children and young people, educationalists, academics, people from business, the third sector and government. Both sessions were held online and followed the format of input, breakout groups and plenary feedback.

Participants were encouraged to familiarise themselves with the Future Schooling, Education and Learning: 2030 and Beyond report and the OECD’s Back to the Future: Four OECD Scenarios for Schooling report. They were also asked to reflect on the beginning of a scenario (Appendix 1) using the following four questions as a guide:

- What do you think will happen?

- What would you like to happen?

- Where are the gaps?

- How would you bridge the gaps?

The first session focused on the questions we should ask ourselves for the next normal in education to emerge. This session was opened by Professor Graham Donaldson, from the University of Glasgow and the International Council of Education Advisers (ICEA).

We then reviewed the output from this session with other work, such as the International Council of Education Advisers Report 2018–20, to identify where we might add most value with our second session.

The follow-up session in February explored the levers, acupuncture and acceleration points for change through the lens of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). The UNCRC was incorporated into Scots Law this year and 2021 is also the Year of Childhood. As the UNCRC has also consistently featured in our work it seemed appropriate to consider how the UNCRC might influence change in school and education, especially school culture and environment.

Providing the input and provocations for this session were Juliet Harris, Director, Together (Scottish Alliance for Children’s Rights), Maxine Jolly, Senior Education Officer, Education Scotland, and Cathy McCulloch, Co-Founder and Co-Director, the Children’s Parliament. They considered how the UNCRC can help reset our mindset and be at the heart of a new normal in Scottish education.

Presentations and Provocations

Session 1: What questions should we be asking ourselves?

Professor Graham Donaldson from the University of Glasgow and the International Council of Education Advisers put forward four propositions to stimulate discussion and debate.

(i) The pandemic’s disruptive impact is accelerating forces of change that were already in place.

The pandemic is accelerating existing pressures, but in a way that will make change hard to predict. These factors include: a world that is more interdependent and competitive than ever; environmental change; social upheaval and inequality; the politics of identity and place; and the new influencers who will shape how we think and act as consumers and citizens. While technology has yet to have a fundamental impact on education, its daily use in ways that are transforming our lives will inevitably influence our thinking about how it could be deployed more radically to enhance teaching and learning.

(ii) The industrial model of education will struggle to survive against the emerging context.

The OECD’s four updated scenarios offer a useful starting point to consider the nature of education and how our current model might change. In the first scenario, schools remain the focal point for formal education but deploy more technology. In the second, some core functions are outsourced to private companies. The third scenario sees schools operate as learning hubs within a much broader context where the wider community is viewed as an important learning resource.

This scenario has some similarities with the scenario in the Future Schooling, Education and Learning: 2030 and Beyond report. In the final scenario of ‘de-schooling’, how people learn is much more fluid, and less focused around the school. The industrial model which has been used for mass learning is likely to struggle in any context that places greater reliance on technology and the wider community. For example, the instructional aspect of education can now be undertaken independently a class teacher. Schools could organise around the differences in prior learning or in how young people learn rather than move groups in a lock-step process. However, any future model needs to build in flexibility from the outset to allow for inevitable change and to recognise the value of school as a social institution and teachers as orchestrators and stimulators of the learning process in ways that also promote wellbeing.

(iii) The educational mission of schools needs to be reasserted, reversing the trend towards training for specific, short-term goals.

The pandemic has brought into sharp focus the need to reassert the education mission of the school. While Curriculum for Excellence, with its four capacities, was partly established to address that very issue, selection pressures have kept the focus on training young people to acquire predetermined content and ultimately to pass exams. In addition, narrow accountability, driven by metrics, tends to restrict the curriculum. Both aspects have detracted from the broader educative and social mission of the school.

(iv) Education for citizenship should be a central purpose of education.

Schools have a significant role to play in supporting young people to be ethical, informed and responsible citizens. This is increasingly important as we move into a period where the fundamental principles of representative democracy are being contested. Schools need to think about how they help young people to understand the forces that are currently shaping our society and to engage in the debate, as well as supporting young people to develop values and ethical stances. That kind of engagement needs to be underpinned by a curriculum that is not afraid to deal with complexity.

Concluding remarks

Professor Donaldson concluded by stating that, although we cannot predict the future, there are issues that we can consider now, to ensure the future is not something that just unfolds but is something that we are proactively engaging with. There is a need for ‘leadership of ideas’. He went on to suggest that the work and approach of the GGiS and SFF collaboration was in a good place to make a significant contribution in this area.

Levers, acupuncture and acceleration points for change

Ahead of session 2, we reviewed the output from session 1 along with the work other groups have completed, such as the International Council of Education Advisers Report 2018–20, to determine where we could best add value. Having taken all this into account, we decided the second part of the conference would focus on the levers, acupuncture and acceleration points for change, through the lens of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC).

Session 2: How can the UNCRC help reset our mindset and be at the heart of a new normal in Scottish Education?

Juliet Harris, Director, Together (Scottish Alliance for Children’s Rights), Maxine Jolly, Senior Education Officer, Education Scotland and Cathy McCulloch, Co-Founder and Co-Director, the Children’s Parliament.

We are at a significant moment in Scotland where the UNCRC is not just something we need to think about: it is something that will be enshrined in law.

Introduction to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC)

The UNCRC is an international law, adopted in 1989 and ratified by the UK Government in 1991. The UNCRC consists of 54 articles (articles 43 to 54 are about how governments and international organisations will work to uphold children’s human rights.) Children have the right to be consulted about all issues that impact on their lives and their views must be taken into account in all our decision-making processes. Children are to be supported to enable them to share their views. There are four general principles that have been pulled out of the UNCRC as a go-to guide. To embed a rights-based approach, we need to think about these four general principles in all of our decisions.

Non-Discrimination – how can we make sure every child has equal opportunity to thrive and develop their full potential?

Best Interests – is the decision I am making and/or the environment I am creating in the best interests of the child?

Children’s Participation – children being asked about a decision and do we feel their voices have been taken into account?

Survival and development – helping children not just to the right to life but the right to thrive, to fulfil their potential to the fullest and to be treated with human dignity.

UNCRC and incorporation into Scots Law

Importantly, children and young people have been key to this journey of securing incorporation of the UNCRC into law in Scotland. The UNCRC is referred to in aspects of policy relating to children and young people, including Getting it Right for Every Child (GIRFEC) and Curriculum for Excellence, but it is only at this point in 2021 that the Scottish

Parliament has passed a Bill to incorporate it into Scots law. Scotland now sits alongside countries such as Norway, Sweden, Iceland and Finland who have all incorporated the UNCRC.

Becoming law means the provisions of the Convention, all 54 rights, can be directly invoked before courts. Therefore, if, in the most serious of cases, children’s rights are breached, children have access to the courts to seek remedy and redress. It does mean that we have to focus on children and young people, if we know that their rights are binding in law.

Whilst a number of children and young people know they have rights, they often feel they are out of reach. They have said that, even if they stand on each other’s shoulders or jump on a trampoline, they are like clouds in the sky: they cannot hold them or hold them true to themselves. Incorporation in law brings these rights into reach, makes them tangible and may help to push a culture change to ensure children’s rights are taken into account in a decision that affects them. This is the case not just in education but in transport, environmental decisions and social security because children are human, and all decisions humans make about humans’ impact on their lives.

UNCRC and education goals

Three main UNCRC articles relate to education, although others have an indirect impact.

Article 28 – every child has the right to education. This must respect children’s dignity particularly when it comes to discipline in school.

Article 29 – the aim of education being the development of the child’s personality, their talents (and interests), their mental and physical abilities, development of respect to the environment, preparing children for a responsible life in a free society with their own cultural identity, language and values. It is important this development is done in a planned and not in an ad hoc way.

Article 31 – relax, play and take part in a wide range of cultural and artistic activities.

At the end of the first lockdown, requests came into Education Scotland from upper primary and lower secondary for professional learning around play pedagogy and how to apply it with older children. How do we let children know it is okay to play and relax, and not something that is bad or frivolous? The UNCRC talks about education being child centred, child friendly, empowering; as something that develops skills, learning, human dignity, self-esteem and self-confidence.

Remembering the UNCRC is a law, which could be perceived as dry, it may be surprising to learn that the introduction to the UNCRC talks about the importance of growing up in a family environment that has an atmosphere of happiness, love and understanding. The family environment is such an important part of children’s lives, and unless the family environment is supported there is no way the children and young people can thrive. That atmosphere of happiness, love and understanding does not just extend to family, it extends to learning environments and schools.

All the presenters observed that much of this approach comes across strongly in the Future Schooling, Education and Learning: 2030 and Beyond report. They also recognised that work was being done to further children’s rights which was not being expressed in these terms. For example, the video clip from Blackburn Primary School, shown at the beginning of session 2, encapsulated a children’s rights approach without mentioning it once. The teacher talked about empowering children and young people and that is what the UNCRC is all about.

However, is this common, embedded practice? The UNCRC seems to have so much potential and if it is a wonderful thing, why hasn’t a children’s rights approach become commonplace In Scotland?

UNCRC and dispelling the myths

The work of the Children’s Parliament has reached some clear understandings about why the UNCRC and a children’s rights approach may not be commonplace. These include a lack of awareness of the UNCRC, how it improves outcomes for children and young people, and finally the perceived status of children in Scotland.

There is a sense that many people see children as people to be done to and done for but very rarely to be done with, and we seldom see children as equal citizens. Often, children are talked about as citizens of the future whereas children talk about being citizens now. It was suggested the culture of Scotland is still predicated on punishment and reward and that there was a need disaggregate that and look at what that actually means and relate it to the outcomes we want to see for children and young people in Scotland.

The myths and misunderstandings common in children’s rights include that children get to do what they want, it risks over-indulging children, and adults lose authority over children. However, children say they need and want boundaries. They also say it is important that they feel adults know what they are doing.

One contributor shared the thoughts of Professor Laura Lundy, from Queen’s University Belfast, who explored adult concerns about pupils’ rights-based participation in educational settings. She found:

Adult concerns tend to fall into one of three groups:

- scepticism about children’s capacity (or a belief that they lack capacity) to have

a meaningful input into decision making,

- worry that giving children more control will undermine authority and destabilise the school environment,

- concern that compliance will require too much effort which would be better spent on education itself. (Lundy 2007 pp. 929–930).

Children’s rights are not about giving things away; it is about making sure that children are happy, healthy and safe and with that comes levels of responsibility on adults to do the right thing.

Visitors to the Children’s Parliament are often surprised by the atmosphere. It is respectful, and children are listening, being kind and taking responsibility. Building relationships between children and adults, and empowering the children, is crucial. In addition, the connection between a sense of wellbeing and the ability to achieve and attain is critical.

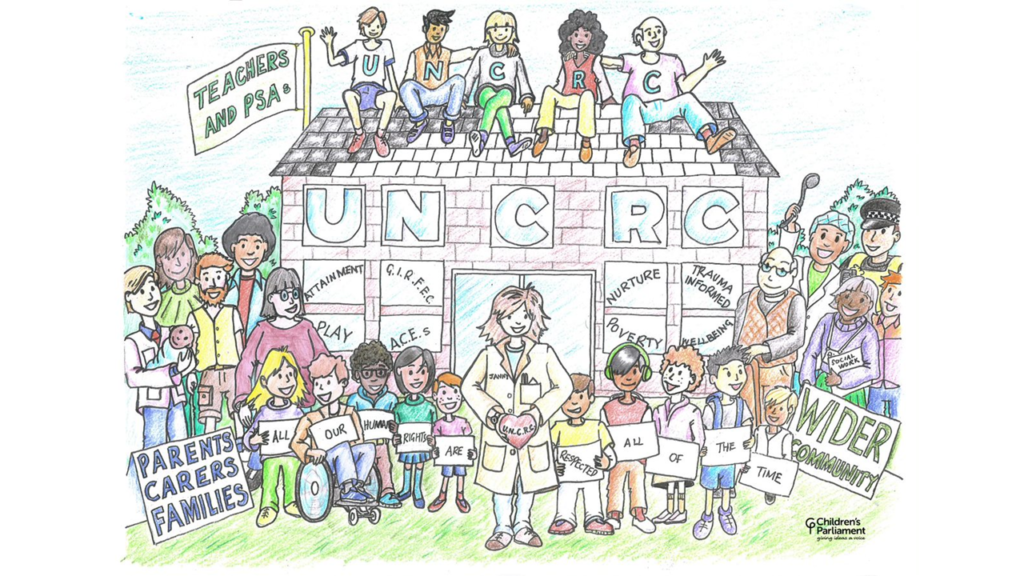

Putting the UNCRC into the bricks

An example was shared of a school using the UNCRC as their guiding principle, the framework against which they measured how we are doing and below which we should not fall. (Appendix 2) All stakeholders in the school and community understand what the UNCRC is, what the benefits are and what the outcomes are for children and the wider community when we embed human rights at the heart of everything we do. By doing this, we automatically recognise trauma and distress in children. Rather than punish poor behaviour, we consider what support we need to provide to help the child deal with their feelings and experiences, and to become more able to self-regulate and

engage positively. In a rights-based environment children feel nurtured, children’s wellbeing is a priority, and staff understand that children living in poverty will experience challenges in their lives and will demonstrate how they feel about that in different ways. These things are taken into account as part of a human-rights approach.

Really importantly, it means it puts human rights in the bricks and the UNCRC provides an insurance policy. It means that, if a new head teacher comes in and pursues their own area of interest, in terms of values and principles of the school, it is more difficult for them to change the culture and ethos of the school because the people in the picture are now empowered to say “We use a human rights approach”. To change that you need to take into account the views of all the children and all the adults connected with the school before you can act. In addition, educators cannot decide to stop empowering children or to introduce a harsh punishment regime. They must adhere to the law to treat children with respect for their human dignity.

A provocation

To stimulate the breakout group discussion at session 2, participants were asked to consider a scenario (Appendix 3). Imagine if a business in 2030 was run like a school in 2021. The scenario was drafted from observations and feedback received by the presenters.

Participants were encouraged to think about the whole-systems approach and culture in Scotland rather than just isolated examples of good or bad practice, reflect on the presentations, the output from session 1 and the Future Schooling, Education and Learning: 2030 and Beyond report and consider the following:

If we consider the UNCRC as a lever and acceleration point for changing the culture and environment in schools (to be less like a workplace 150 years ago and more like a workplace in the future) then:

- What do we need to keep/lose/introduce?

- What are the challenges and the tensions?

- What are some of the solutions to these challenges and tensions?

- What do we need to do differently to make sure we are where we need to be in 2030?

Incorporation of the UNCRC as a lever for change

Can the incorporation of the UNCRC help facilitate and support change in the education system?

In considering the incorporation of the UNCRC as a potential lever and acceleration point for change in education, we have reviewed the views, ideas and questions collected at both conference sessions and the Future Schooling, Education and Learning: 2030 and Beyond report to look for connections and/or a relationship with the UNCRC and a rights-based approach to education.

The aim and purpose of education in Scotland

There was a suggestion during the conference that we should have one narrative for education, and Professor Donaldson proposed the broad educational mission of schools in Scotland needs to be reasserted. Whilst achieving one narrative may be challenging, could the incorporation of UNCRC help with this as the guiding principle for the purpose of education and school? Does it have the right language? As an example, education for citizenship was suggested as a central purpose of education. Whilst we need to understand what we mean by citizenship, the UNCRC says children have the right to participate as “an active agent in their own lives and in society”.

Perhaps we need to consider the difference between ‘citizenship education’ – usually a curricular subject taught by an educator – and being empowered to be a citizen? This comes from being considered an equal, contributing person with agency in a school environment.

Could this be the time to raise awareness of the UNCRC and its potential as a terms of reference for reviewing the purpose of education in Scotland and as an anchor for a new narrative?

As one contributor said, “children are citizens now and not citizens in waiting.”

A child-centred approach

Throughout the current work of the GGiS/SFF community, several phrases have been prevalent in describing not only what the future of schooling, education and learning might look like but also how the next normal in education might emerge. These phrases are flexibility, co-creation, creativity, inclusion and equity, culture, trust and relationships. All of these have a connection or relationship with the UNCRC.

Flexibility

Flexibility has been suggested in:

Curriculum and Pedagogy

The discussions highlighted a number of areas to consider, including having a flexible education system that supports all children, such as the child who thrives on routine, the child who thrives on being given creative space and the child who requires additional support to thrive. To be learner led, children and young people need to be able to learn through a passion or interest, using their curiosity as a foundation to build the curriculum and not be restricted by a 50-minute period.

Interdisciplinary Learning was highlighted, utilising a mixture of approaches with digital, online, outdoor/indoor, school and community learning the norm in any future education system. This means letting children and young people decide the approaches that motivate them, with technology and digitalisation just one tool in a toolbox of approaches. However, it was acknowledged that having digitalisation and technology as an option allows for education and learning across borders – global and local.

Children and young people want to be connected to, supported by and challenged by professional educators and, where appropriate, educators from the wider community.

Some of the children and young people agreed structure was needed if there was a clear purpose for that structure. It was suggested that purpose should be pedagogy. Ideas included working in project teams, including multi-aged groups and learners matched with the educators who can best support them. An example was shared where students in S1 were given a maths test, not to look at their level of learning but the way they worked. They were then matched with an educator who could best support them.

One discussion group also suggested it may be valuable to look at what subjects children and young people have been willingly engaging with during the Covid-19 lockdown and which ones are they leaving to one side.

The development of life skills also featured strongly throughout discussions, with some young people feeling ill-equipped to make the transition from school, whether it be to further/higher education or employment. For one young person, it took a gap year to help develop attributes, such as empathy, compassion and the ability to plan. Again, it was acknowledged that this would not be the experience of every young person but highlights the question: how can education, learning and school be a positive experience for all?

If we agree that 21st-century life requires us to be curious and questioning, have agency, be creative and think critically, these are skills and values that have to be inculcated and supported throughout

childhood. They cannot suddenly be taught as young people approach the end of secondary school.

This point was echoed by one participant who added that, whilst it is important for all young people to feel confident when leaving school, trust, empathy, kindness, and respect need to start in early years and be followed through all stages of education.

School Design

The industrial model of school has shown itself to be resilient, but Professor Donaldson suggested this model will struggle to survive intact against the emerging context. A universal design, for school and the system, with built in flexibility, sits well with a rights-based approach as it would have the potential to support the needs of all children and

young people. There was also strong agreement that personal interaction matters, and any future model of school must have a physical element for socialising.

With this in mind, is it also time to look at the school day and year to meet the needs of education and learning? How appropriate is a school year based on the agricultural calendar? The impact of Covid-19 and the increase in digital learning/online learning indicates that some young people have felt empowered and able to take control of their day, have lunch when they want and participate when they want. How can we explore this further in helping the next normal in education to emerge?

Measuring attainment and achievement

The emerging future has big implications for the way we examine and assess young people and reflect that in qualifications. This has been highlighted throughout our work. Some young people would like to see exams replaced with a portfolio of work that presents a true picture of themselves. However, others feared the amount of power given to educators and this approach being open to prejudice. Perhaps the answer lies somewhere in between with a flexible, individualised approach to measuring attainment and achievement. This may have helped two participants, who, for different reasons, did not feel they had fulfilled their potential. One believed they had not been

challenged enough to the degree that they did not think they needed to study, and as a result they did

not achieve the exam grades expected. The second young person believed their potential had been underestimated.

In the Future Schooling, Education and Learning: 2030 and Beyond report, we suggest Scotland could explore the impact and opportunities if the exam system was abandoned, and undertake a review with employers, colleges and universities to identify an alternative currency based around the four capacities.

Co-creation

The voices and participation of children and young people are integral to the UNCRC.

Are we truly listening to children and young people’s views and ideas? Are we creating environments where children and young people feel safe and have agency to share their views and experiences? And can they do this when it is important for them to do it, rather than in the half hour slot allocated by an educator? Are we involving them in decisions that impact them or is, as one group suggested, the amount of attention paid to the voices of children and young people in education tokenistic?

Children and young people want to be able to choose their education, rather than have schooling and education done to them or other people choosing on their behalf. We need to move away from a culture that asks if a child is ready for school, to a one which asks if the school is ready for the child.

Embedding the UNCRC into everything we do in school and education provides the opportunity for meaningful involvement by children and young people, such as co-creating curriculum and the culture of the school, thereby making a school a great place for everybody to learn and work.

The latest research by Mannion, Sowerby & I’Anson (2020) identifies four interlinked arenas of participation by children and young people: “the formal curriculum, the wider curriculum, decision making groups and linking with the wider community”. The research highlights how participation and a rights-based approach to education can have a positive impact on attainment and achievement, wellbeing and behaviour.

Inclusion and equity

How can education, learning and school be a positive experience for all children and young people? As a society, we need to do the best by our children and young people who have challenges of where they come from. There was agreement that removing barriers, such as digital poverty, could help improve inclusion and equity for children and young people. This is an area now covered by the UNCRC.

The incorporation of the UNCRC and a rights-based approach could provide the opportunity to reimagine

children’s services including education. That could include a multi-agency approach that has hubs open all year for children and young people who need it.

Creativity

The need for creativity and innovation by all stakeholders in education has been highlighted throughout discussions. Some examples have been shared as part of this conference. Innovation and creativity have also been identified as key 21st-century skills. Therefore, it makes sense to encourage and provide space for creativity and innovation in school and education. Allowing educators and children to experiment with different approaches and techniques as part of the curriculum would help children and young people develop this attribute. The Future Schooling, Education and Learning: 2030 and Beyond report suggests an Education Incubator. Professor Donaldson talks about the need for the “leadership of ideas”. It would be important and critical for children and young people to participate in this type of idea generation and experimentation.

Culture

‘Putting the UNCRC into the bricks’ could help facilitate positive cultural change in schools by engaging all stakeholders in the school – helping to put the school at the heart of the community. Are there any lessons we can learn from community schools?

The ‘business run like a school’ scenario exercise (Appendix 3) provoked a mixed reaction from participants. Some did not recognise the practices, highlighted in the slide, in their school, whereas others had experience of all or some of the practices. Examples shared included the use of behaviour reward charts in class, such as the rocket or rainbow. A child’s behaviour determined their position on the rocket or, in the case of the rainbow chart, whether they were in the sunshine (good behaviour) or on a dark cloud (less desirable behaviour). This raised the question ‘Why we are too frightened to recognise these types of practices still exist?’

It was proposed that a school could use the ‘business run like a school’ slide as a measure of the cultural health of the school. To ask themselves – how much are we like this? Educators and learners could complete the exercise separately then compare the results. It was agreed it is important to listen to and observe children and young people to find out what they are thinking and feeling about these types of provocations.

Other contributors suggested schools were rule heavy, although there was agreement that boundaries are important. Moving forward, there was a call for children and young people to be involved in co-creating the rules and boundaries in their school. Any rules and boundaries agreed should be based on respect and trust, and apply to all in the school community. This would help empower children and young people and encourage ownership and responsibility.

Children and young people want to retain the fun and enjoyment in education as it helps engagement and believe it leads to success. It becomes a virtuous cycle, and parallels were drawn with a business that is successful, when customers flood to them. The children and young people believed fun and enjoyment in school would have a positive impact on the school and their learning.

Trust and relationships

Developing trusting relationships between children, young people and their educators are fundamental to embedding the UNCRC. However, throughout this work the overarching theme required to effect positive change in the education system is to develop trust across all those who have a stake in the education system.

There is a need to explore how we, as a society, do this. Could the full incorporation of the UNCRC be an opportunity to do this and get everybody on the same page?

What are the challenges and tensions?

The challenge of embedding the UNCRC is not underestimated. We still have some way to go to progress towards a truly humanised education system. However, we have the opportunity with the incorporation of the UNCRC to influence system change that is consistent and sustainable. It is not saying every school must be the same, like a fast food franchise, but that what the children and young people will experience consistently and sustainably is respect, kindness, trust and respect for their human dignity in whatever environment they are in. Let us engage people in this conversation, explain what it means, and encourage them to try some of this for themselves. Only in the extreme do we

have to go down the criminal justice route. It will also mean that, as change is explored, we start from a child-rights and child-centred positioning. Other challenges and tensions include:

Education, government agencies, politics and empowerment

During our discussions, the role of party politics in education has been raised on several occasions. Some contributors perceive politicians as using education as a ‘political football.’ For others, the question is about guidance – what is the right level of guidance from government agencies in relation to education?

There is sense there is an imbalance of power and authority with too many layers moderating what schools and educators do, with structures still vested in a pyramid shape. Even with the introduction of the Regional Improvement Collaboratives, do educators feel more empowered in the current environment? What changes need to happen for the potential of the Regional Improvement Collaboratives to be maximised?

Could flatter structures help redress the balance between power and authority, and help build trust and agency? The aim for educators to be ‘excited, energised and motivated’ by the challenge. Would this agency help educators to embed a rights approach in their school, and engage and empower children and young people?

Initial teacher education and professional development

Where next for initial teacher education (ITE) and professional development of educators? It is acknowledged that great progress has been made with ITE and professional development – with career long professional learning in place. In adopting a rights-based approach, what is in place for educators to understand their responsibilities and be supported in their development? Will professional standards be amended to take account of the UNCRC?

Resources

How can a child-centred approach be implemented when resources are limited, and school is based on an industrial model? The adoption of a universal school design may help, and change certainly requires investment in resources (human and material) to be effective. Do we need to review the model of funding for our education system? How have other countries that have incorporated the UNCRC funded their education system? What lessons can we learn?

In terms of the present, how do we keep the show on the road while creating space for educators to think proactively and creatively about the future, to debate, discuss, to innovate and experiment? In the Future Schooling, Education and Learning: 2030 and Beyond report we suggested we could introduce a professionally educated para educator role, akin to the roles seen in professions, such as law and medicine.

Pace of change

It was noted how quickly the education system has changed over the past year, so perhaps change could move at a faster pace? One contributor noted that there had been gradual change in curriculum making to encompass skills, such as collaboration, communication, creativity, productivity and critical thinking to equip young people with the skills necessary to navigate their lives beyond compulsory education.

Is it a case of considering the type and pace of change we want? The questions asked at the beginning of this conference were: will the next normal in education follow the current approach to formal education and schooling but doing this more effectively? Or, as a society, will we take the opportunity to review the purpose of education and school to ensure it is relevant and sustainable for the 21st century? From our discussions there was a sense we are ready for something more radical, but should this be a revolution or an evolution?

Next Steps

This is not so much a call for action but a call for deep listening, and an openness to ideas, by everyone involved school, education and the wider community. When it comes to education and school, our work has shown the incredible talent and experience we have within and out-with the education system in Scotland. These people have great ideas and thinking. How do we harness this energy and foster an environment of sharing and cooperation, to engage with potential accelerators for change, such as the UNCRC?

Does this mean we need another national debate or conversation about the future of school and education? Or has this conversation already started organically? Our work and the work of others, some of which is highlighted in this report, would suggest it has.

Therefore, perhaps the question is: how do we distil the fruits of these conversations and engage with the sources of power in society, who ultimately determine the way in which things shape up in the future?

Could a Citizens’ Assembly for education and school help facilitate this? Could this approach provide a participative framework to listen, discuss and make clear proposals about the future of education and schooling in Scotland? Could this approach enable us to bring everything to the table: the potentially controversial topics, such as denominational and independent schools, as well as the great ideas and thinking already taking place in Scotland? There is definitely plenty to explore.

References

Greg Mannion, Matthew Sowerby & John I’Anson (2020): Four arenas of school-based participation: towards a heuristic for children’s rights-informed educational practice, Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, DOI: 10.1080/01596306.2020.1795623

Laura Lundy (2007): ‘‘Voice’ is not enough: conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child’, British Educational Research Journal, 33:6, 927–942

Appendix 1. Mini Scenario: COVID-19

Many of the people at the citizens’ assembly were children and teenagers at the time of the pandemic. They reminisced about learning at home with online resources and cancelled exams. Parents and carers tried to provide them with support whilst adapting to new ways of working themselves, which for many was working from home unless, of course, they were a key worker. The children of key workers and vulnerable children went to the forerunner of the learning hubs we see today in 2030.

At the time of Covid-19, there was ongoing concern that the attainment gap would only get wider as children and young people from disadvantaged backgrounds fell through the cracks. Digital poverty was also highlighted as a major issue and barrier.

Over two years from 2020 to 2022, the people of Scotland battled, innovated, created and learned to live with the ongoing threat of Covid-19. Many educators responded to the challenges with many examples of innovative practice. Early in the pandemic, some were completely adrift due to a lack of experience and/or technology, but as educators got to grip with the situation they fully converted to online teaching, adapting and finding new ways of doing things at a local level and collaborating with sectors to bring in the appropriate expertise, such as the creative industries. They were excited, energised and motivated by the challenge.

It was a rollercoaster ride for all. After the first national lockdown was followed by some local lockdowns, in early 2021 there was a second peak of the infection rate, which led to another national lockdown. Although many people found this a further challenge, they were at least better prepared when this was gradually eased again. The inevitable economic downturn began to bite, with winners and losers across all sectors and an increase in unemployment.

There was also recognition of the fact that we couldn’t lose sight of other disrupters and mega trends such a climate change and technology. One of glimmer of hope from the pandemic was that sustainability issues came into sharp focus. In a short period, society was seeing and experiencing the environmental impact of less travel with cleaner air and nature in recovery. Also, through necessity, technology, especially online communication platforms, was being embraced.

From the beginning of the pandemic, everybody talked about a next normal, a sense things would never be the same again. What would the next normal be for education and schooling, and how would we get there?

- What happened next?

- What do you think will happen?

- What would you like to happen?

- Where are the gaps?

- How would you bridge the gaps?

Appendix 2

Appendix 3. Imagine if in 2030 businesses and industry were structured and run like a school in 2021

Some provocations

- When you arrive at work in the morning you have to stand outside whatever the weather and line up to get in.

- You have to change your shoes before you enter your office or workplace.

- When you receive your brief for the day you have to sit on the floor whilst your line manager sits on a chair.

- You have no choice in the order in which you complete your daily tasks.

- You only have your breaks and lunch at a certain time, when a bell rings.

- You only go to the toilet at specific times, and if you need to go out-with, you have to ask permission in front of your colleagues and explain why you didn’t go earlier.

- If your line manager is not happy with your performance would the following happen?

- You would have your name written up in a board in the office.

- You would be made to go and stand in the corridor.

- The Director would come and loudly remove you from the office.

- You would be shouted at in front of all your colleagues.

- You would not get the chance to explain your actions or quietly apologise.

- Someone else leaves dirty dishes in the sink – they don’t own up so the whole office has to miss their coffee break.

- At the end of a tiring day you long to spend time relaxing with your family or friends, instead you have to read a document that is of no interest to you and write a report on it for the next day.

What do we need to change in our schools to make them less like a workplace of 150 years ago, and more like a work place of the future? What do we need to lose/introduce?

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our speakers and discussion group reporters for their contribution and support.

Speakers

Professor Graham Donaldson, University of Glasgow, ICEA and the Goodison Group in Scotland

Juliet Harris, Director, Together (Scottish Alliance for Children’s Rights)

Maxine Jolly, Senior Education Officer, Education Scotland

Cathy McCulloch, Co-Founder and Co-Director, Children’s Parliament

Discussion Group Reporters

Keir Bloomer, Education Consultant

Isabelle Boyd, Executive Director, Cor ad Cor

Liam Fowley MSYP, Vice Chair, Scottish Youth Parliament

Gillian Hunt, Education Consultant

Valerie Jackman, Leadership Lead, College Development Network

Neil McLennan, Senior Lecturer and Director of Leadership Programmes, University of Aberdeen

Elizabeth McGuire, Senior Education Officer, Education Scotland

Jane Minelly, Head Teacher, Bothwellpark High School, Motherwell

Ken Muir, Chief Executive, General Teaching Council, Scotland

With very special thanks to:

The GGiS/SFF Community

All those who sent us a video clip

Emma Quinn Design

Una Bartley, Creative Writer

Bryan and Craig Fleming, FJ Philanthropy, our Zoom hosts